Daniel Levy was the most influential man at Tottenham Hotspur for the best part of a quarter of a century.

That’s why when it was communicated that Levy would be stepping down from his role as executive chairman of the club on September 4, and moving back from all leadership roles at Spurs, although keeping his shareholding, it was a seismic development at a club who have seen enormous growth off the pitch, but less so on it during the Levy reign.

Levy has been very vocally criticised by Spurs, especially in recent months, with the perceived lack of investment in the product on the pitch when the club has grown enormously off it, the cause of much ire among Spurs fans. The goodwill that arrived from the delivery of a world-class stadium in 2019 dissipated pretty swiftly as the product on the pitch failed to match what surrounded them.

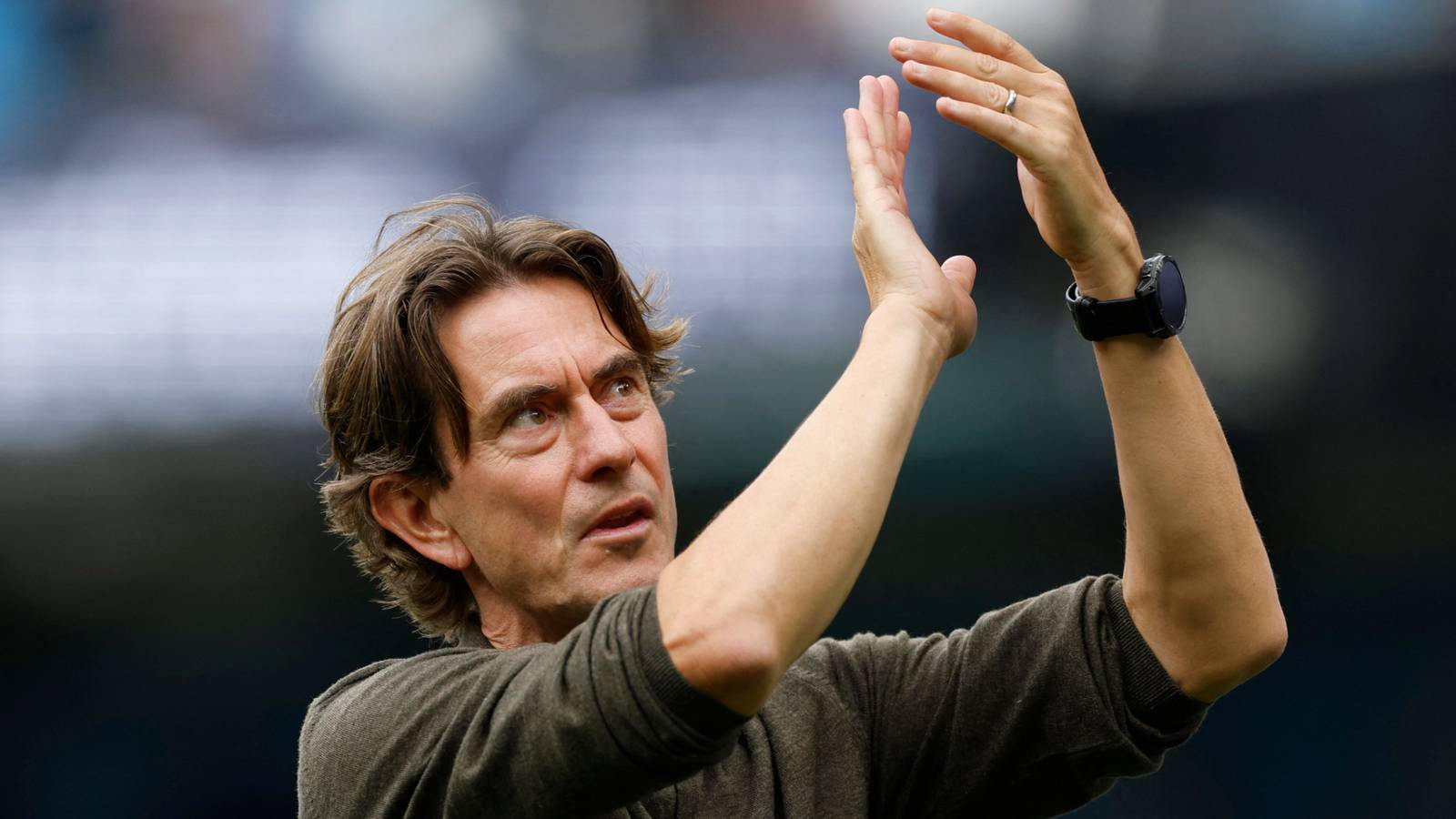

A succession of managers came and went after the departure of the popular Mauricio Pochettino, with Jose Mourinho, Nuno Espirito Santo, Antonio Conte, Ange Postecoglou and, now, Thomas Frank being tasked with delivering glory.

Levy was seen as someone who kept too tight a grip on the purse strings. But does the data back that up? Between 2019 and 2024, the most recently published financial accounts from the football club, Spurs had a gross transfer spend of £830m, putting them fifth out of the so-called ‘big six’, with Liverpool behind them. As of 2024, the squad cost was also the highest that it had ever been at the club, sitting at almost £700m, up from the £579m it had been 12 months previously. Since 2016, the squad cost at the club had risen 298%, from £175m.

But, Levy is now out of Spurs, at least from holding any influence or operational control, and the focus, for the first time for a while, has been placed back on the owners of the football club - ENIC, rather than the former chairman, who served as something of a lighting rod for criticism when it came to the Joe Lewis-owned ENIC enterprise.

Tottenham Takeover Rumours Continue

Rumours of a potential takeover at Spurs have swirled round for a long time. Ever since the completion of the stadium, done at a time before interest rates and the cost of borrowing shot up, Spurs has been seen as a prime piece of football real estate. A club nestled in North London, with transport links, a dense urban population in one of the world’s most populous cities, a stadium that had been completed and had long-term contracts with the likes of the NFL in place, the ability to host multiple concerts per year, heightened chance of European football and a manageable payroll in comparison to their rivals.

Jahm Najafi’s MSP Sports Capital had been linked with a purchase back in 2023 at a price north of £3bn, but that particular deal never materialised. The same can be said for reported interest from one-time Manchester United bidder Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad al-Thani, while former Newcastle United co-owner Amanda Staveley has long been rumoured to be spearheading an investment play on behalf of a Middle Eastern consortium.

American tech entrepreneur Brooklyn Earick recently ‘launched’ a £4.5bn takeover bid, only for Spurs to distance themselves from such a bid, and Earick and his backers said to have withdrawn interest after being given firm rebuttal from the Lewis family.

Tottenham in Line for Further £75m Boost After £100m Injection

Last week saw the club get a £100m cash injection from ENIC. The reason: “to equip the club’s leadership team with additional resources to continue the focus on driving long-term sporting success”. What that boils down to, essentially, is investment in the playing squad in a bid to make the team, which has had an encouraging start under Frank, more competitive.

For Spurs, being a part of the Champions League this season is a major boon. The best case scenario for Spurs this season, taking into account prize money, participation fees, the value pillar, matchday revenue and their record in the competition already, is north of £130m. That would require a flawless record from here on in and winning the whole competition. Conservatively, the club can expect to bank more than £75m just by making it through to the knockout stages, which they are backed to do.

But for Spurs to be investing sustainably in the first team, they need to marry the competitive success with the commercial and matchday success, something that hasn’t been forthcoming at the level fans or ownership would have wanted to see. Regular qualification for the Champions League year in, year out, just as has been achieved at Arsenal in more recent years after a period out in the cold, is transformative for finances, allowing clubs to absorb bigger wages and transfer fees, placing less emphasis on boom or bust seasons.

Would the £100m have arrived if Spurs hadn’t made the Champions League this season by virtue of winning the Europa League last season? Potentially, but the reality is that the additional funds, the change of mood and leadership points to them believing that this season will be far better than the last, and that obtaining a spot in the top four of the Premier League, potentially the top five if European performance warrants it, come the end of 2025/26 is attainable.

£100m ENIC Injection Not a Transfer Kitty

It can be very easy to look at that £100m in isolation, treating it as the amount of money that is at hand in 2025/26 to strengthen the team. Not a bad sum, of course, but in a landscape where some of Spurs’ rivals broke the British transfer record twice in a matter of weeks at £116.5m and then £125m, it maybe doesn’t go as far as it once did.

But the £100m doesn’t reflect a £100m transfer kitty. What it will allow for is the club to cashflow these deals far more easily, meaning that they will have readily available, tangible cash to meet initial payments or some pre-existing transfer debt. In many cases, clubs that have access to cash and can pay more upfront have better leverage.

It’s important to take into account that club owners inject cash into their teams not just to fund big signings but to strategically position their teams in the transfer market. While some of that money may go toward settling existing transfer debt—often structured as staggered payments over several years—the primary aim is to create liquidity. This liquidity allows clubs to act decisively when opportunities arise, whether that’s securing a priority target or outmanoeuvring rivals in a competitive bidding scenario. It is often a game of chess in the transfer market.

Transfer debt itself is a common feature of modern football finance. Clubs routinely agree to pay fees in instalments, which helps manage cash flow but also creates future obligations. While transfers are accounted for on the balance sheet through the process of amortisation, where the guaranteed sum of a deal is divided by the years of the player’s contract, decreasing by a year’s cost with every passing season, real money is required to pay these deals down over time. When owners inject fresh capital, it can be used to meet these obligations without compromising short-term competitiveness. More importantly, it allows clubs to offer upfront payments for new deals, which are often preferred by selling clubs. This reduces reliance on credit facilities or third-party financing, which can be costly or restrictive.

Having tangible cash on hand significantly improves a club’s negotiating power. Sellers favour buyers who can pay quickly and in full, as it reduces risk and administrative burden. Clubs with cash can also leverage discounts, secure better payment terms, or jump queues for in-demand players. In a market where speed and certainty matter, liquidity isn’t just a financial advantage—it’s a strategic one. That’s why injections like ENIC’s £100m into Spurs are framed as tools for “long-term sporting success” rather than just balance sheet patchwork.

But it likely won’t all be accounted for to be put to work for new additions. Spurs have a pretty weighty £337m or so transfer debt issue that has to be addressed.

Tottenham Second Only to Manchester United

Spurs’ reputation for financial caution in the Levy era doesn’t quite match the numbers. Since taking charge, Levy oversaw the generation of a staggering £1.6bn in operating cash flow, second only to Manchester United in English football. That’s not the mark of a club scraping by—it’s the sign of a well-oiled commercial machine. Yet Spurs have consistently spent less on transfers than their rivals, choosing instead to funnel cash into long-term infrastructure like the £1.2bn Tottenham Hotspur Stadium and the club’s training ground.

This strategy has created a funding gap that wasn’t filled by owner equity, but by debt. Spurs now carry £851m in financial debt and £337m in transfer debt, the highest combined figure in the Premier League. That transfer debt reflects deferred payments on past signings—not reckless overspending, but structured deals designed to preserve short-term liquidity. It’s a model that prioritises sustainability, but it’s also built on leverage.

The irony? Levy was often criticised for being risk-averse, yet Spurs have embraced debt more aggressively than most. Their cash flow statement tells the story: strong operating performance, modest squad investment, and heavy borrowing to support growth. Even ENIC’s £100m cash injection wasn’t about splashing out—it was a tactical move to ease liquidity pressure and maintain flexibility in the market.

In today’s transfer landscape, tangible cash is king. Clubs that can offer upfront payments get better deals, faster negotiations, and more leverage. Spurs’ ability to generate cash gives them that edge—but their choice to use it for infrastructure rather than squad inflation has defined the Levy era. Now that era is over, perhaps an early play to quell any unrest around the owners, who remain adamant that they do not want to sell the football club, is to make moves that suggest some more focus will be placed on aiding Frank’s bid to bring silverware to the club and to solidify its position in the Champions League on a regular basis.